Dundee, IL January 4, 2021.

On December 17, 1978 I was a 12-year old managing our family’s choose & cut Christmas tree farm, while my father fed the cattle on a cold winter morning. During a break from customers, I looked towards the house, waiting for Dad to relieve me so I could have some lunch. But instead of seeing him walking across the field and across the road towards me, family friend and neighboring nurse Medrith’s car was at our house–she was the one to whom everyone turned during medical emergencies.

My father had suffered a heart attack and full cardiac arrest. We were about 40-miles and an hour’s drive from the nearest cardiac care facility in Wichita, and once called, it took a half hour for the volunteer-service ambulance to arrive.

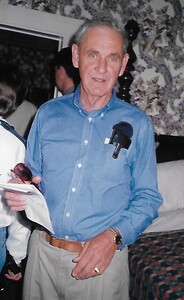

At that time, the survival rate for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was 8.6%. Today it is about 9.9%. My father miraculously survived, underwent a triple bypass operation in February of 1979, and was with us until a non-heart-related issue took him from us in 2003.

While my father was not shoveling snow when he “got sick” as we termed it, according to Harvard University, shoveling snow significantly increases the risk for heart attacks and death.

As an Ergonomist, I have experimented with various ways of “better snow shoveling” over the years. From an energy expenditure standpoint, shoveling snow requires a lot of effort and can increase the risk for heart attacks, as dense snow weighs up to 20-lbs per cubic foot and, obviously, people are working in cold temperatures, also a risk factor. The ice/snow mix we received between Christmas and New Year’s 2020/21 made the job even more difficult, as a cubic foot of ice can weigh as much as 57-lbs. Since many people shovel using only their upper extremities and use large shovels, there is a lot more stress on the cardiovascular system.

Frederick Taylor, the founder of the science of modern ergonomics, was noted for his 1881 study of people shoveling coal into furnaces. Coal weighs about 80- to 85-lbs per cubic foot, more than ice or snow, but Taylor’s lesson is important: By using a smaller shovel for the coal, he found that people could shovel more coal with less overall physical exertion than when using larger “scoop” shovels.

Sometimes a smaller shovel is better.

So how do Taylor’s 140-year-old Victorian findings apply to shoveling snow in the 21st Century?

- For light, fluffy snow, a large snow shovel may be appropriate

- For heavy snow or ice, use a smaller shovel (less weight/less energy expenditure)

- When moving snow, put the shovel on the ground and walk forward as much as possible before emptying it (the legs are stronger than the arms and this technique reduces overall energy expenditure)

- Use the lower thigh just above the knee as a fulcrum, so instead of using the arm muscles to lift the scoop of snow, the lever action magnifies your force application, thus reducing energy expenditure

- If you have enough snow each year and can afford one, use a snow blower (or “rent” one from a neighbor) (Even an inexpensive electric shovel-style snow blower can reduce your physical efforts)

- If you can afford the help and are in an at-risk group, hire it done

- If you’re unable to do any of these things, reach out to a local service group or Scouts BSA Troop (Scouts are always looking for service work to do)

- An “ergonomic” style shovel is also an option, but not necessarily a “must-have”

James Pottorff.

I grew up a lot that winter many years ago, but I was among the lucky ones. I cannot imagine what life would have been like without my father around, and am thankful that day was not “his time” to leave this earth.

Please do your best to apply these lessons and ideas the next time you have to shovel snow, ice, or do something else requiring a lot of exertion.

For more information on what I do, and how my team and I can help you, please contact me at info@qp3ergosystems.com or directly at +1 (847) 921-3113.